Designing Data Intensive Applications Notes: Ch.1 Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Applications

aboelkassem | October 30, 2023

Hello, this is a new series of articles for my notes and summaries of the “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” book by Martin Kleppmann.

In this article, we will walkthrough the first chapter of this book Chapter.1 Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Applications.

Table Of Content (TOC)

CPU power is rarely the limiting factor anymore, it is the data size that is.

A data-intensive application is typically built from standard building blocks that provide commonly needed functionality. For example, many applications need to:

- Store data so that they, or another application, can find it again later (databases)

- Remember the result of an expensive operation, to speed up reads (caches)

- Allow users to search data by keyword or filter it in various ways (search indexes)

- Send a message to another process, to be handled asynchronously (stream processing)

- Periodically crunch a large amount of accumulated data (batch processing)

Thinking About Data Systems

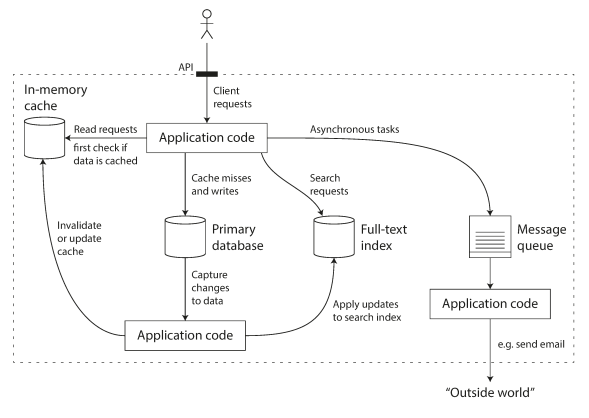

Many new tools for data storage and processing have emerged in recent years. They are optimized for a variety of different use cases, and they no longer neatly fit into traditional categories. For example, there are datastores that are also used as message queues (Redis), and there are message queues with database-like durability guarantees (Apache Kafka). The boundaries between the categories are becoming blurred.

If you have an application-managed caching layer (using Memcached or similar), or a full-text search server (such as Elasticsearch or Solr) separate from your main database, it is normally the application code’s responsibility to keep those caches and indexes in sync with the main database.

Reliability

System should continue to work correctly, even in the face of faults and human errors.

The things that can go wrong are called faults, and systems that anticipate faults and can cope with them are called fault-tolerant or resilient.

Note that a fault is not the same as a failure. A fault is a one component of the system deviating from its specs, while failure is the when the system as a whole stops working. It’s impossible to prevent faults, but we should try to prevent faults from causing failures by designing fault-tolerance mechanisms.

The Netflix Chaos Monkey is an approach to continued test the app for handling faults.

Hardware Faults

Hard disks crash, RAM becomes faulty, the power grid has a blackout, someone unplugs the wrong network cable.

To Solve it, you need to add redundancy to the individual hardware component. Disks may be set up in a RAID configuration, servers may have dual power supplies and hot-swappable CPUs, and datacenters may have batteries and diesel generators for backup power.

There is a move toward systems that can tolerate the loss of entire machines, by using software fault-tolerance techniques in preference or in addition to hardware redundancy.

Software Errors

The reason behind software faults is making some kind of assumptions about the environment, this assumptions are usually true, until the moment they are not. There is no quick solution to the problem, but the software can constantly check itself while running for discrepancy.

For example:

- A software bug that causes every instance of an application server to crash when given a particular bad input. For example, consider the leap second on June 30, 2012, that caused many applications to hang simultaneously due to a bug in the Linux kernel.

- A runaway process that uses up some shared resource—CPU time, memory, disk space, or network bandwidth.

- A service that the system depends on that slows down, becomes unresponsive, or starts returning corrupted responses.

Human Errors

Some approaches for making reliable systems, in spite of unreliable human actions include:

- Design systems in a way that minimizes opportunities for error. For example, well-designed abstractions, APIs, and admin interfaces make it easy to do “the right thing” and discourage “the wrong thing.”

- Provide fully featured sandbox environments with real data for testing, without affecting real users.

- Test throughly at all levels, from unit tests, to whole system integration tests.

- Make it fast to roll back configuration changes, and provide tools to re-compute data.

- Use proper monitoring that shows early warnings signals of faults (telemetry is essential for tracking what is happening, and for understanding failures).

- Implement good management practices and training.

Scalability

As system grows, there should be reasonable ways for dealing with that growth.

Describing Load (Twitter example)

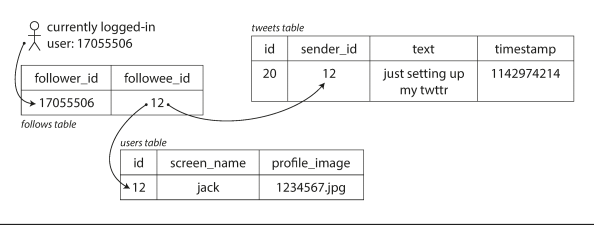

In Nov 2022, Two of Twitter’s main operations are:

- Post tweet: A user can publish a new message to their followers (4.6k requests/sec on average, over 12k requests/sec at peak)

- Home timeline: A user can view tweets posted by the people they follow (300k requests/sec).

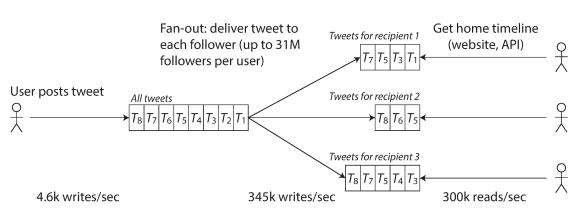

Handling 12K writes/sec would be easy, the main challenge with twitter scaling is fan-out (each user follows many people, and each user is followed by many people)

Approach 1 is simply write query to get user home timeline when a user requests their home timeline. look up all the people they follow, find all the tweets for each of those users, and merge them.

SELECT tweets.*, users.* FROM tweets

JOIN users ON tweets.sender_id = users.id

JOIN follows ON follows.followee_id = users.id

WHERE follows.follower_id = current_user

Approach 2 was maintaining a cache for each user’s home timeline. When a user posts a tweet, look up all the people who follow that user, and insert the new tweet into each of their home timeline caches.

First version of Twitter used approach 1, but the systems struggled to keep up with the load of home timeline queries, so the company switched to approach 2. This works better because the average rate of published tweets is almost two orders of magnitude lower than the rate of home timeline reads.

The downside of approach 2 is that posting a tweet now requires a lot of extra work. On average, a tweet is delivered to about 75 followers, so 4.6k tweets per second become 345k writes per second to the home timeline caches. If user have 30 million followers, this means single tweet may take over 30 million writes to home timelines.

Twitter is moving to a hybrid of both approaches. Most users’ tweets continue to be fanned out to home timelines at the time when they are posted, but a small number of users with a very large number of followers (i.e., celebrities) are excepted from this fan-out. Tweets from any celebrities that a user may follow are fetched separately and merged with that user’s home timeline when it is read, like in approach 1.

Describing Performance

Throughput is the most important metric in batch processing systems, while response time is the most important metrics for online systems.

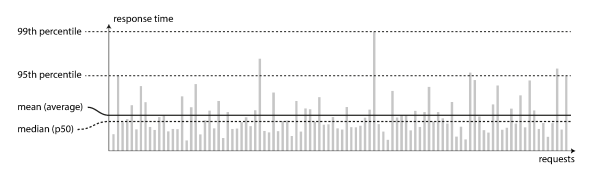

The following image Illustrating mean and percentiles: response times for a sample of 100 requests to a service.

Most requests are reasonably fast, but there are occasional outliers that take much longer. Perhaps the slow requests are intrinsically more expensive, e.g., because they process more data, loss of network packets, TCP retransmission or a garbage collection pause.

A common performance metric is percentile, where Xth percentile = Y ms means that X% of the requests will perform better than Y ms. It’s important to optimize for a high percentile, as customers with slowest requests often have the most data (eg. purchases). However, over optimizing (eg. 99.999th ⇒ the slowest 1 in 10,000 requests) might be too expensive.

It’s important to measure response times on client side against realistic traffic size.

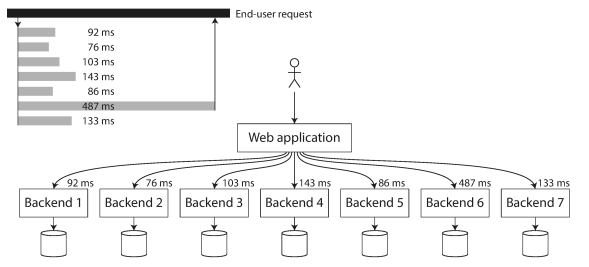

In distributed systems, effect of tail latency amplification can happen (When several backend calls are needed to serve a request, it takes just a single slow backend request to slow down the entire end-user request and you must wait until all calls ended)

Approaches for Coping with Load

Some systems are elastic, meaning that they can automatically add computing resources when they detect a load increase, whereas other systems are scaled manually (a human analyzes the capacity and decides to add more machines to the system). An elastic system can be useful if load is highly unpredictable, but manually scaled systems are simpler and may have fewer operational surprises

While distributing stateless services across multiple machines is fairly straightforward, taking stateful data systems from a single node to a distributed setup can introduce a lot of additional complexity. For this reason, common wisdom until recently was to keep your database on a single node (scale up) until scaling cost or high availability requirements forced you to make it distributed.

In an early stage startup, it’s more important to be able to iterate quickly on product features than to scale to some hypothetical future load.

Maintainability

Different people who works on the system should all be able to work on it productively

To minimize pain during maintenance, there are some design principles take into your consideration.

-

Operability: Make it easy for operations teams to keep the system running smoothly.

- Good monitoring

- Providing good support for automation and integration with standard tools

- Avoiding dependency on individual machines

- Good documentation

- Keeping software and platforms up to date, including security patches

- Providing good default behavior, while giving administrators the option to override

- Self-healing, while giving administrators a manual control

-

Simplicity: Make it easy for new engineers to understand the system, by removing as much complexity as possible from the system.

- A good system should be simple, this can be done by reducing complexity, which doesn’t necessarily mean reducing its functionality, but rather by making abstractions.

- good abstraction can hide a great deal of implementation detail behind a clean, simple-to-understand façade.

- A good abstraction can also be used for a wide range of different applications.

-

Evolvability: Make it easy for engineers to make changes to the system in the future, adapting it for unanticipated use cases as requirements change

- Agile is one of the best working patterns for maintaining evolvable systems.

- Test-driven development (TDD) and refactoring also used for evolvability