Designing Data Intensive Applications Notes: Ch.10 Batch Processing

aboelkassem | November 04, 2023

Continuing our series for “Designing Data-Intensive Applications” book.

In this article, we will walkthrough the second chapter of this book Chapter.10 Batch Processing.

Table of content (TOC)

- Batch Processing with Unix Tools

- The Output of Batch Workflows

- Comparing Hadoop to Distributed Databases

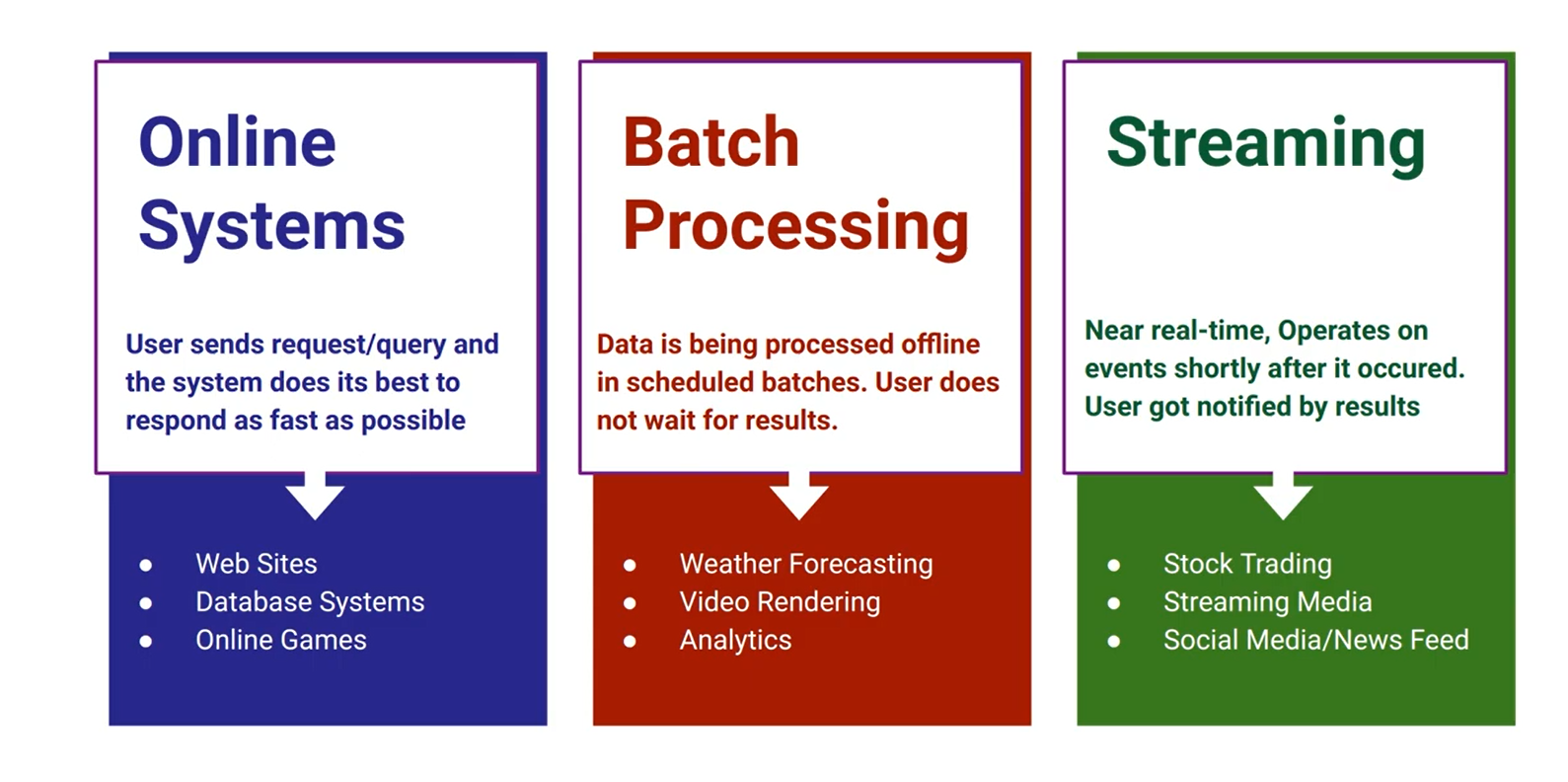

All systems can fit into three main categories:

- Services (online), where it waits for requests from a client to arrive, tries to handle them as quickly as possible, and sends back a response.

- Batch Processing Systems (offline), takes a large amount of input data where it runs a job to process a large amount of bounded input, and produce some output data. It is often scheduled periodically, and can take up to several days as no user is typically waiting for it to finish.

- Stream Processing Systems (near-real-time), Stream processing is somewhere between online and offline/batch processing, where is consumes unbounded input/events shortly after its available, processes it, and produces output. It build upon batch processing and have lower latency.

In this chapter, we will look at MapReduce and several other batch processing algorithms and frameworks.

Batch Processing with Unix Tools

Say you have a web server that appends a line to a log file every time it serves a request.

216.58.210.78 - - [27/Feb/2015:17:55:11 +0000] "GET /css/typography.css HTTP/1.1" 200 3377 "http://martin.kleppmann.com/" "Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_9_5) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/40.0.2214.115 Safari/537.36"

$remote_addr - $remote_user [$time_local] "$request" $status $body_bytes_sent "$http_referer" "$http_user_agent"Many data analysis can be done in few minutes using some combination of Unix commands awk, sed, grep, sort, uniq, and xargs.

for example the following command, can find the five most popular pages on your website

cat /var/log/nginx/access.log |

awk '{print $7}' |

sort |

uniq -c |

sort -r -n |

head -n 5- Line 1: read the log file

- Line 2: Split each line into fields by whitespace, take the seventh field ⇒ like string.split(” ”)[6] in c# …. awk is scripting language

- Line 3: Sort the list alphabetically.

- Line 4: Filter out repeated lines, -c print the counter for every distinct URL.

- Line 5: Sort by the number (-n which is repeated times) in reverse order (-r)

- Line 6: take the first five lines

The output of command will be like

4189 /favicon.ico

3631 /2013/05/24/improving-security-of-ssh-private-keys.html

2124 /2012/12/05/schema-evolution-in-avro-protocol-buffers-thrift.html

1369 /

915 /css/typography.cssA uniform interface

A compatible interface. If you want to be able to connect any program’s output to any program’s input, that means that all programs must use the same input/output interface.

In Unix, that interface is a file (or, more precisely, a file descriptor). A file is just an ordered sequence of bytes. Because that is such a simple interface, can be an actual file on the filesystem, a communication channel to another process (Unix socket, stdin, stdout), a device driver (say /dev/audio or /dev/lp0), a socket representing a TCP connection, and so on.

By convention, many Unix programs treat this sequence of bytes as ASCII text. The above example treat their input file as a list of records separated by the \n (newline, ASCII 0x0A).

The good thing is that interface give the a shell user to wire up the input and output in whatever way they want; you can even write your own program/tool (just need follow the interface by reading input from stdin and writing the output to stdout)

Reasons that Unix tools are so successful includes that the input files are treated as immutable, we can end the pipeline are any point, and we can write the output of intermediate stages to files for fault-tolerance.

The biggest limitation of Unix tools is that it can only run on a single machine, that’s where tools like Hadoop come in.

MapReduce and Distributed Filesystems

MapReduce is a bit like Unix tools, but distributed across potentially thousands of machines. While Unix tools use stdin and stdout as input and output, MapReduce jobs read and write files on a distributed filesystem. In Hadoop’s implementation called HDFS (Hadoop Distributed File System).

Various other distributed filesystems besides HDFS exist, such as GlusterFS and the Quantcast File System (QFS). Object storage services such as Amazon S3, Azure Blob Storage, and OpenStack Swift are similar in many ways.

There is two approaches for storing files

- Network Attached Storage (NAS) and Area Network (SAN) architectures: implemented by a centralized storage appliance (hardware or Fibre channel).

- Shared-Nothing principle (horizontal scaling): requires no special hardware, only computers connected by a conventional datacenter network.

HDFS is based on the shared-nothing principle. Which consists of a daemon process running on each machine exposing a network service that allows other nodes to access files stored on that machine. A central server called the NameNode keeps track of which file blocks are stored on which machine. In order to tolerate machine and disk failures, file blocks are replicated on multiple machines.

MapReduce Job Execution

MapReduce is a programming framework with which you can write code to process large datasets in a distributed filesystem like HDFS. The previous example of Unix log analysis, this how data processing in MapReduce.

- Read a set of input files, and break it up into records. In the web server log example, each record is one line in the log (that is, \n is the record separator).

- Call the mapper function to extract a key and value from each input record. In the preceding example, the mapper function is awk ‘{print $7}’: it extracts the URL ($7) as the key, and leaves the value empty.

- Sort all of the key-value pairs by key. In the log example, this is done by the first sort command.

- Call the reducer function to iterate over the sorted key-value pairs. If there are multiple occurrences of the same key, the sorting has made them adjacent in the list, so it is easy to combine those values without having to keep a lot of state in memory. In the preceding example, the reducer is implemented by the command uniq -c, which counts the number of adjacent records with the same key

Those four steps can be performed by one MapReduce job. Steps 2 (map) and 4 (reduce) are where you write your custom data processing code. Step 1 (breaking files into records) is handled by the input format parser. Step 3, the sort step, is implicit in MapReduce—you don’t have to write it, because the output from the mapper is always sorted before it is given to the reducer.

To create a MapReduce job, you need to implement two callback functions, the mapper and reducer, which behave as follows:

- Mapper: called once for every input record, its job is to extract the key and value from the input record.

- Reducer: takes the key-value pairs produced by the mappers, collects all the values belonging to the same key, and use them to produce a number of output records.

The role of the mapper is to prepare the data by putting it into a form that is suitable for sorting, and the role of the reducer is to process the data that has been sorted

MapReduce can parallelize a computation across many machines. The mapper and reducer only operate on one record at a time; they don’t need to know where their input is coming from or their output is going to.

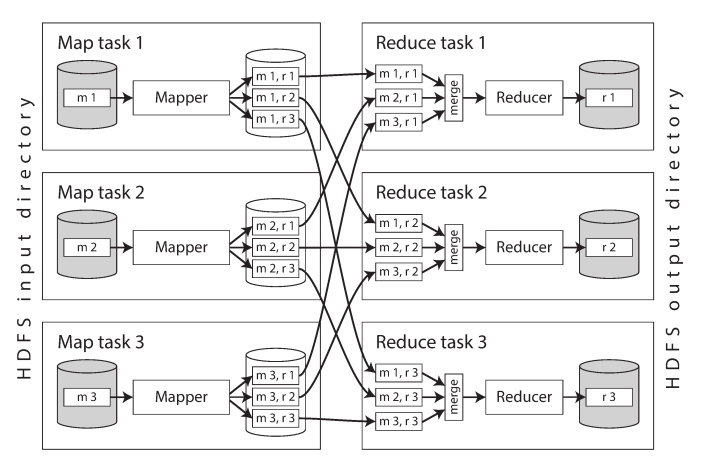

The following diagram shows the dataflow in Hadoop MapReduce job. The input is a directory in HDFS and each file is separate partition that can be processed by a separate map task (m1, m2, m3)

Application code (e.g., JAR files if java application) is run in the map task and the MapReduce framework first copy this code to the appropriate machines, then starts the map task and begins reading the input file, passing one record at a time to the mapper callback. The output of the mapper consists of key-value pairs.

The key-value pairs must be sorted, but the dataset is likely too large, Instead, the sorting is performed in stages. First, each map task partitions its output by reducer, based on the hash of the key. Each of these partitions is written to a sorted file on the mapper’s local disk. The reducers connect to each of the mappers and download the files of sorted key-value pairs for their partition.

The reduce task takes the files from the mappers and merges them together, preserving the sort order. Thus, if different mappers produced records with the same key, they will be adjacent in the merged reducer input

MapReduce jobs cannot have any randomness, and the range of problems we can solve with single MapReduce job is limited, so commonly jobs are chained together to form a workflow (output of one job becomes the input to the next job), Hadoop MapReduce framework does not have any particular support for workflows, so it done implicitly using directory names.

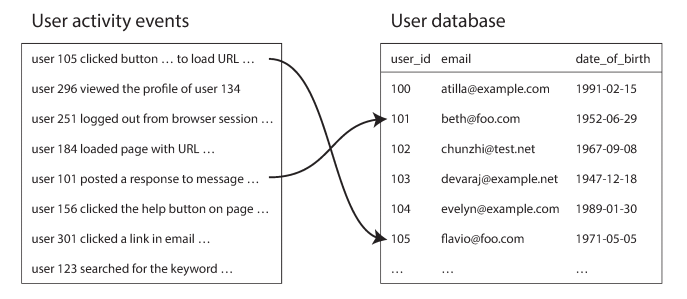

Joins in batch processing

Joins are necessary whenever we need to access records on both sides of an association, but MapReduce has no concept of indexes to help in the join operation. it reads the entire content of the file.

For example: analysis of user activity events, On the left is a log of events and on the right is a database of users.

To do joins is to query the file needed for join over the network (go over the activity events one by one and query the user database (on a remote server) for every user ID), however such an approach is most likely to suffer from poor performance, and also can lead to inconsistency if the data changes over the time of round-trip for remote database. So, a better approach would be to clone the other database into the distributed system (using ETL (Extract, Transform, Load) process).

Sort-merge joins

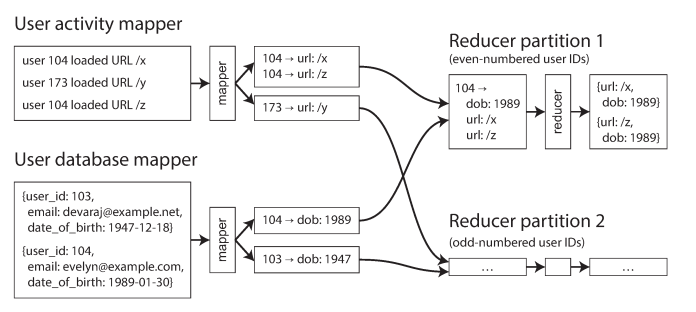

Now, we have in the distributed filesystem user database and user activity records. The mapper will extract a key-value pair for each input from activity events (key = userID, value= activity event) and from user database (key = userId, value = user’s data like birth of data)

MapReduce partitions the mapper output by key and then sorts it to become adjacent to each other in the reducer input. The reducer can then perform the actual join logic easily: the reducer function is called once for every user ID. The first value is expected to be the date-of-birth record from the user database and now can get viewers-age-in-years for viewed-url. Reduce jobs could then calculate the distribution of viewer ages for each URL, and cluster by age group.

Since the reducer processes all of the records for a particular user ID in one go, it only needs to keep one user record in memory at any one time, and it never needs to make any requests over the network. This algorithm is known as a sort-merge join, since mapper output is sorted by key, and the reducers then merge together the sorted lists of records from both sides of the join.

Bringing related data together in the same place like what mappers docs can be a fairly simple, single-threaded piece of code that can churn through records with high throughput and low memory overhead. Besides joins, MapReduce can handle also grouping records by some key.

Skewed/hot key can happened in single reducer (for example in social media and celebrity has millions of records). Since a MapReduce job is only complete when all of its mappers and reducers have completed, any subsequent jobs must wait for the slowest reducer to complete before they can start.

To Solve hot keys, When performing the actual join, the mappers send any records relating to a hot key to one of several reducers, chosen at random.

Map-Side Joins

The merge-sort join approach has the advantage that you do not need to make any assumptions about the input data: whatever its properties and structure, the mappers can prepare the data to be ready for joining. However, the downside is that all that sorting, copying to reducers, and merging of reducer inputs can be quite expensive. Depending on the available memory buffers, data may be written to disk several times as it passes through the stages of MapReduce.

if you can make certain assumptions about your input data, it is possible to make joins faster by using a so-called map-side join. This approach uses a cut-down MapReduce job in which there are no reducers and no sorting. Instead, each mapper simply reads one input file block from the distributed filesystem and writes one output file to the filesystem—that is all.

There are two approaches to perform map-side joins

- Broadcast hash joins

- Partitioned hash joins

The Output of Batch Workflows

The output of a batch process is often not a report, but some other kind of structure

Building search indexes

Google’s original use of MapReduce was to build indexes for its search engine, which was implemented as a workflow of 5 to 10 MapReduce jobs. They moved away for it for this purpose. but still Hadoop MapReduce remains a good way of building indexes for Lucene/Solr.

If you need to perform a full-text search over a fixed set of documents, then a batch process is a very effective way of building the indexes: the mappers partition the set of documents as needed, each reducer builds the index for its partition, and the index files are written to the distributed filesystem. This will make query parallelizes very well.

Another common use for batch processing is to build machine learning systems such as classifiers (e.g., spam filters, anomaly detection, image recognition) and recommendation systems. The output of those batch jobs is often some kind of database: for example, a database that can be queried by user ID to obtain suggested friends for that user, or a database that can be queried by product ID to get a list of related products

These databases need to be queried from the web application that handles user requests, which is usually separate from the Hadoop infrastructure. So how does the output from the batch process get back into a database where the web application can query it?

A much better solution is to build a brand-new database inside the batch job and write it as files to the job’s output directory in the distributed filesystem and can be loaded in bulk into servers that handle read-only queries. Various key-value stores support building database files in MapReduce jobs, including Voldemort, Terrapin, ElephantDB, and HBase bulk loading.

When loading data into Voldemort, the server continues serving requests to the old data files while the new data files are copied from the distributed filesystem to the server’s local disk. Once the copying is complete, the server atomically switches over to querying the new files. If anything goes wrong in this process, it can easily switch back to the old files again.

The Unix-like philosophy in MapReduce has many advantages, as we can simply rollback any changes with the guarantee of the producing the same output when the job runs again, feature development can proceed more quickly, it transparently retries failed tasks without affecting the application logic, it provides a separation of concerns, and the same set of files can be used as inputs for different jobs.

Comparing Hadoop to Distributed Databases

Hadoop is somewhat like a distributed version of Unix, where HDFS is the filesystem and MapReduce is a quirky implementation of a Unix process.

Hadoop has often been used for implementing ETL processes, MapReduce jobs are written to clean up that data, transform it into a relational form, and import it into an MPP data warehouse for analytic purposes.

Database

- Require you to structure data according to a particular model

- monolithic, tightly integrated pieces of software that take care of storage layout on disk, query planning, scheduling, and execution.

- If a node crashes while a query is executing, most MPP databases abort the entire query, and either let the user resubmit the query

Hadoop

- Distributed filesystem are just byte sequences

- Batch processes are less sensitive to faults than online systems, because they do not immediately affect users if they fail and they can always be run again.

- Can tolerate the failure of a map or reduce task without it affecting the job as a whole by retrying work at the granularity of an individual task.

SQL query language allows expressive queries and elegant semantics without the need to write code. not all kinds of processing can be sensibly expressed as SQL queries. For example, if you are building machine learning and recommendation systems, or full-text search indexes. These kinds of processing are often very specific to a particular application (e.g., feature engineering for machine learning, natural language models for machine translation, risk estimation functions for fraud prediction), so they inevitably require writing code, not just queries.

MapReduce gave engineers the ability to easily run their own code over large datasets. If you have HDFS and MapReduce, you can build a SQL query execution engine on top of it.

Beyond MapReduce

Various higher-level programming models (Pig, Hive, Cascading, Crunch) were created as abstractions on top of MapReduce. MapReduce is very robust: can process large quantities of data for multi-tenant system and will get the job done (but slowly and poor performance). Other tools are sometimes orders of magnitude faster for some kinds of processing.

Materialization of Intermediate State

Intermediate state: is when you know the output of one job is only ever used as input to one other job which maintained by the same team. In the complex workflows used to build recommendation systems consisting of 50 or 100 MapReduce jobs there is a lot of such intermediate state.

MapReduce’s approach is fully materialized, which means to eagerly compute results of some operations and write them out rather than computing them on demand. This prevents any job from starting until all its preceding jobs are completed, mappers are often redundant, and this extra intermediate storage have to be replicated which wastes a lot of resources.

Dataflow engines (eg. Spark, Tex, Flink, etc.) fixed MapReduce disadvantages by handling and entire workflow as one job, rather than small independent sub-jobs. Like MapReduce, they work by repeatedly calling a user-defined function to process one record at a time on a single thread. They parallelize work by partitioning inputs, and they copy the output of one function/operator over the network to become the input to another function/operator. It also provides more flexible callback functions (operations) rather than only map and reduce.

This style of processing engine is based on research systems like Dryad and Nephele which can do in-place sorting when required only. there are no unnecessary map tasks, and other advantages.

We can use dataflow engines to implement the same computations as MapReduce, but it executes significantly faster. However, because they dismiss the intermediate materialization, they have to to recompute most of the data when the job fails. However, the re-computation overhead of dataflow engines makes it challenging to use it with small data or CPU-intensive computations, so materialization would be cheaper.

Pregal Processing modal is an an optimization for batch processing graphs it is implemented by Apache Giraph, Spark’s GraphX API, and Flink’s Gelly API. It is also known as the Pregel model.

Higher-level languages and APIs (eg. Hive, Pig) has the advantages of requiring less code, while also allowing interactive use. Moreover, it also improves the job execution efficiency at the machine level.

Batch processing has an increasingly important applications in statistical and numerical algorithms, machine learning, recommendation systems, and computing spatial algorithms as well.

In batching processing techniques that read a set of files as input and produce a new set of output files. The output is a form of derived data; that is, a dataset that can be recreated by running the batch process again if necessary. We saw how this simple but powerful idea can be used to create search indexes, recommendation systems, analytics, and more.